Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) due to obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)1

There are multiple disruptions to consider when treating EDS due to OSA1-3

Airway obstruction

CPAP can address the airway issues of OSA, but EDS may persist in patients despite compliant use.1,2

of patients in a study reported feeling sleepy during the day even after using CPAP2*†

patients who used their CPAP ≥5 hours a night still reported feeling tired during the day2*

Neurological disruption

Patients with OSA experience chronic intermittent hypoxia and sleep fragmentation, which are thought to cause neuronal injury in wake-promoting neurotransmitters that may lead to long-term impairments in wakefulness.3,4

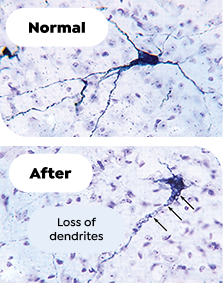

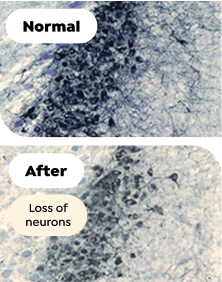

NEURONAL INJURY IN ANIMAL MODELS OF OSA

Impaired wakefulness persisted after returning to normal sleep activity, indicating long-lasting neuronal injury3,4

Chronic Intermittent Hypoxia3‡

Intermittent hypoxia caused dendritic loss in wake-promoting dopaminergic and noradrenergic neurons in mice

Chronic Sleep Fragmentation4§

Mice with chronic sleep fragmentation had reduced numbers of wake-promoting noradrenergic neurons

The clinical relevance is not known.

CPAP=continuous positive airway pressure.

*In a study of 174 patients with moderate-to-severe OSA using CPAP, daytime sleepiness was assessed before and after 3 months of CPAP therapy using the Epworth Sleepiness Scale.2

†Average CPAP use ranged from 2 or fewer hours per night to 7 or more hours per night.2

‡Hypoxia/reoxygenation in adult mice for 8 weeks, modeling severe sleep apnea. Arrows show vacuolization in soma adjacent to dendrites and dendritic beading.3

§Exposure to sleep disruptions over 14 weeks caused a significant reduction of wake-promoting noradrenergic neurons compared with the control group (P<0.001), even after 4 weeks of recovery.4

EDS due to OSA can impact your patient’s life in multiple ways5

~9 out of 10 patients with EDS due to OSA reported that their EDS impacted their work, social life, and relationships*

7 out of 10 patients with EDS due to OSA reported that their condition impaired their driving*

Many patients with residual EDS due to OSA reported a decline in overall physical and mental well-being*

See potential impact*Among 6 focus groups conducted with 42 participants currently experiencing EDS with OSA, 62% were currently using a positive airway pressure (PAP) or dental device (n=26/42).5

EDS in OSA may also be due to other factors, such as chronic sleep loss and comorbid disorders2,6

See how neurotransmitter dysregulation can affect the sleep-wake cycle

The American Thoracic Society recommends routine assessment of daytime sleepiness in patients with OSA7

Assess your patients’ EDS with the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS)8-10

A validated method to screen for, identify, and monitor EDS in OSA

Identifying excessive daytime sleepiness

An ESS score of >10 indicates EDS9

The ESS is a validated, patient-reported measure of the patient's likelihood of falling asleep during 8 daily activities, including reading, watching television, and driving9

Download the ESSDiagnosis of persistent EDS in OSA is based on a clinical assessment, which must be made by the treating physician. The diagnosis must be made after airway treatment is implemented and all other causative disorders have been considered. These include other untreated sleep disorders, mental disorders, or the effects of medications.11

The Maintenance of Wakefulness Test (MWT)

Used in clinical and research settings to assess EDS in patients with OSA12

The MWT is an objective measure that evaluates a patient’s ability to remain awake while1:

These 40-minute trials are repeated several times, separated by 2-hour breaks. Cumulative time equals total “wakefulness minutes.”1

Four to five 40-minute trials, conducted over the course of 1 day

INDICATION AND IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION

INDICATION

SUNOSI is indicated to improve wakefulness in adults with excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) associated with narcolepsy or obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

LIMITATIONS OF USE

SUNOSI is not indicated to treat the underlying obstruction in OSA. Ensure that the underlying airway obstruction is treated (e.g., with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP)) for at least one month prior to initiating SUNOSI. SUNOSI is not a substitute for these modalities, and the treatment of the underlying airway obstruction should be continued.

IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION

CONTRAINDICATIONS

SUNOSI is contraindicated in patients receiving concomitant treatment with monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), or within 14 days following discontinuation of an MAOI, because of the risk of hypertensive reaction.

WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

Blood Pressure and Heart Rate Increases

SUNOSI increases systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and heart rate in a dose-dependent fashion.

Blood Pressure and Heart Rate Increases (Cont’d)

Epidemiological data show that chronic elevations in blood pressure increase the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), including stroke, heart attack, and cardiovascular death. The magnitude of the increase in absolute risk is dependent on the increase in blood pressure and the underlying risk of MACE in the population being treated. Many patients with narcolepsy and OSA have multiple risk factors for MACE, including hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and high body mass index (BMI).

Assess blood pressure and control hypertension before initiating treatment with SUNOSI. Monitor blood pressure regularly during treatment and treat new-onset hypertension and exacerbations of pre-existing hypertension. Exercise caution when treating patients at higher risk of MACE, particularly patients with known cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, pre-existing hypertension, and patients with advanced age. Use caution with other drugs that increase blood pressure and heart rate.

Periodically reassess the need for continued treatment with SUNOSI. If a patient experiences increases in blood pressure or heart rate that cannot be managed with dose reduction of SUNOSI or other appropriate medical intervention, consider discontinuation of SUNOSI.

Patients with moderate or severe renal impairment could be at a higher risk of increases in blood pressure and heart rate because of the prolonged half-life of SUNOSI.

Psychiatric Symptoms

Psychiatric adverse reactions have been observed in clinical trials with SUNOSI, including anxiety, insomnia, and irritability.

Exercise caution when treating patients with SUNOSI who have a history of psychosis or bipolar disorders, as SUNOSI has not been evaluated in these patients.

Patients with moderate or severe renal impairment may be at a higher risk of psychiatric symptoms because of the prolonged half-life of SUNOSI.

Observe SUNOSI patients for the possible emergence or exacerbation of psychiatric symptoms. Consider dose reduction or discontinuation of SUNOSI if psychiatric symptoms develop.

MOST COMMON ADVERSE REACTIONS

The most common adverse reactions (incidence ≥5%) reported more frequently with the use of SUNOSI than placebo in either narcolepsy or OSA were headache, nausea, decreased appetite, anxiety, and insomnia.

Dose-Dependent Adverse Reactions

In the 12-week placebo-controlled clinical trials that compared doses of 37.5 mg, 75 mg, and 150 mg/day of SUNOSI to placebo, the following adverse reactions were dose-related: headache, nausea, decreased appetite, anxiety, diarrhea, and dry mouth.

DRUG INTERACTIONS

Do not administer SUNOSI concomitantly with MAOIs or within 14 days after discontinuing MAOI treatment. Concomitant use of MAOIs and noradrenergic drugs may increase the risk of a hypertensive reaction. Potential outcomes include death, stroke, myocardial infarction, aortic dissection, ophthalmological complications, eclampsia, pulmonary edema, and renal failure.

Concomitant use of SUNOSI with other drugs that increase blood pressure and/or heart rate has not been evaluated, and combinations should be used with caution.

Dopaminergic drugs that increase levels of dopamine or that bind directly to dopamine receptors might result in pharmacodynamic interactions with SUNOSI. Interactions with dopaminergic drugs have not been evaluated with SUNOSI. Use caution when concomitantly administering dopaminergic drugs with SUNOSI.

USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

Renal Impairment

Dosage adjustment is not required for patients with mild renal impairment (eGFR 60-89 mL/min/1.73 m2). Dosage adjustment is recommended for patients with moderate to severe renal impairment (eGFR 15-59 mL/min/1.73 m2). SUNOSI is not recommended for patients with end stage renal disease (eGFR <15 mL/min/1.73 m2).

ABUSE

SUNOSI contains solriamfetol, a Schedule IV controlled substance. Carefully evaluate patients for a recent history of drug abuse, especially those with a history of stimulant or alcohol abuse, and follow such patients closely, observing them for signs of misuse or abuse of SUNOSI (e.g., drug-seeking behavior).

SUN HCP ISI 05/2022

Please see full Prescribing Information.

REFERENCES:

- SUNOSI (solriamfetol) [prescribing information]. New York, NY: Axsome Therapeutics, Inc.

- Antic NA, Catcheside P, Buchan C, et al. The effect of CPAP in normalizing daytime sleepiness, quality of life, and neurocognitive function in patients with moderate to severe OSA. Sleep. 2011;34(1):111-119.

- Zhu Y, Fenik P, Zhan G, et al. Selective loss of catecholaminergic wake-active neurons in a murine sleep apnea model. J Neurosci. 2007;27(37):10060-10071.

- Zhu Y, Fenik P, Zhan G, Xin R, Veasey SC. Degeneration in arousal neurons in chronic sleep disruption modeling sleep apnea. Front Neurol. 2015;6:109.

- Waldman LT, Parthasarathy S, Villa KF, Bron M, Bujanover S, Brod M. Understanding the burden of illness of excessive daytime sleepiness associated with obstructive sleep apnea: a qualitative study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18(1):128.

- Slater G, Steier J. Excessive daytime sleepiness in sleep disorders. J Thorac Dis. 2012;4(6):608-616.

- Strohl KP, Brown DB, Collop N, et al. An official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline: sleep apnea, sleepiness, and driving risk in noncommercial drivers. An update of a 1994 statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(11):1259-1266.

- Ahmed IM, Thorpy MJ. Clinical evaluation of the patient with excessive sleepiness. In: Thorpy MJ, Billiard M, eds. Sleepiness: Causes, Consequences and Treatment. Cambridge University Press; 2011:36-49.

- Johns MW. About the ESS. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://epworthsleepinessscale.com/about-the-ess/

- Johns M, Hocking B. Daytime sleepiness and sleep habits of Australian workers. Sleep. 1997;20(10):844-849.

- Chapman JL, Serinel Y, Marshall NS, Grunstein RR. Residual daytime sleepiness in obstructive sleep apnea after continuous positive airway pressure optimization: causes and management. Sleep Med Clin. 2016;11(3):353-363.

- Arand D, Bonnet M, Hurwitz T, Mitler M, Rosa R, Sangal RB. The clinical use of the MSLT and MWT. Sleep. 2005;28(1):123-144.

- Zhou J, Camacho M, Tang X, Kushida CA. A review of neurocognitive function and obstructive sleep apnea with or without daytime sleepiness. Sleep Med. 2016;23:99-108.

- Vasudev P, Arjun P, Azeez AK, Nair S. Prevalence of cognitive impairment in obstructive sleep apnea and its association with the severity of obstructive sleep apnea: a cross-sectional study. Indian J Sleep Med. 2020;15(4):55-59.

- Werli KS, Otuyama LJ, Bertolucci PH, et al. Neurocognitive function in patients with residual excessive sleepiness from obstructive sleep apnea: a prospective, controlled study. Sleep Med. 2016;26:6-11.

- Grandner MA, Min JS, Saad R, Leary EB, Eldemir L, Hyman D. Health-related impact of illness associated with excessive daytime sleepiness in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Postgrad Med. 2023;135(5):501-510.

- Grandner MA, Min JS, Saad R, Leary EB, Eldemir L, Hyman D. Health-related impact of illness associated with excessive daytime sleepiness in patients with obstructive sleep apnea [supplementary appendix]. Postgrad Med. 2023;135(5):501-510.

- Lee SA, Han SH, Ryu HU. Anxiety and its relationship to quality of life independent of depression in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. J Psychosom Res. 2015;79(1):32-36.

- Joo EY, Tae WS, Lee MJ, et al. Reduced brain gray matter concentration in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep. 2010;33(2):235-241.

- Xiong Y, Zhou XJ, Nisi RA, et al. Brain white matter changes in CPAP-treated obstructive sleep apnea patients with residual sleepiness. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2017;45(5):1371-1378.

- Saper CB, Scammell TE, Lu J. Hypothalamic regulation of sleep and circadian rhythms. Nature. 2005;437(7063):1257-1263.

- Schwartz JRL, Roth T. Neurophysiology of sleep and wakefulness: basic science and clinical implications. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2008;6(4):367-378.

- Franco-Pérez J, Ballesteros-Zebadúa P, Custodio V, Paz C. Principales neurotransmisores involucrados en la regulación del ciclo sueño-vigilia [Major neurotransmitters involved in the regulation of sleep-wake cycle]. Rev Invest Clín. 2012;64(2):182-191.

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders. 3rd ed. American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014.